It’s easy to learn when you’re obsessed.

Chances are, if you’re reading this, you’re really good at something. It was a passion — a calling — that tackled you emotionally, that wouldn’t let you rest until you figured it out. It certainly took time and effort, and there were times it was challenging, but it didn’t feel hard, exactly, because you were so intent. The hours just disappeared. You never got bored.

Giftedness researchers call this intensity the ‘rage to master.’

It’s both a blessing and a curse.

It’s a blessing because it helps you be really good at something… and without a lot of perceived drudgery, yay!

But… possessing just one superlative skill gives you just one career option: Find someone to pay you to do that one thing, and that thing only. In other words, put all your eggs in one basket — someone else’s basket.

With a more diversified portfolio of skills, however, you could build your own damn basket factory. A beowulf cluster of comfy egg hammocks woven from a plurality of clients and customers. The kind of career that’s bomb-proof.

Just imagine what you could achieve if you could not only do your thing, but also teach, connect, persuade, market, sell.

There’s just one problem:

You’ve tried to bulk out your skill set, and… it got hard, and you gave up.

When you hit the skill gap — that jagged chasm between what I can do right now and what I need to be able to do to achieve my goals — you fell in and couldn’t see your way out.

“Why would anyone want to subscribe to me,” you told yourself, or “I just can’t write sales copy for shit,” or “I’ll never be able to learn to design/code/market/sell things. It’s too hard.”

(Not a lot of folks have rage to master marketing as their first love.)

Instead of raging to master, you rage quit.

The very strength that made things so effortless for you before has paradoxically made your skill acquisition muscles weak and under-developed.

Once you’ve experienced mastery in one arena — that came “effortlessly,” or so it seemed — learning something the long, hard way feels like drudgery and punishment.

There’s a reason most child prodigies wash out: They have one very specific skill, developed to the exclusion of all others… which means it’s nearly impossible for them to carve out a place for themselves in the broader marketplace of adults.

(There’s also a reason for the enduring popularity of the ‘wildly passionate, overconfident, reality-distorting workaholic founder’ trope. That’s just ‘rage to master’ by another name… plus or minus a personality disorder.)

But… hey! You’re not a child. You’re an adult. You’re not a slave to your momentary feelings of hatethissomuch.

You can identify the problem and implement a plan to fix it.

Good news: That’s why I’m here. We’re gonna fix that vicious cycle right now!

I’m going to teach you how to easily and quickly pick up competence in new skills that don’t light your fire.

Especially skills that help connect you with other people, like teaching, marketing, and selling.

I’m also going to show you how to avoid the pitfalls that undermine those of us spoiled by rage to master.

Without further ado, let’s talk about gaining rapid competence in things that kinda bore you! Aka skilling up.

Let’s set the scene: Our metaphor today will be food. Because who doesn’t like food? Everyone eats food, and knows what food looks like; many can judge superlative food from merely good or even mediocre food; and some have the rage to master food.

I am definitely not one of them.

I’m a recipe tweaker, but not much of an inventor. I don’t enjoy spending hours at the stove, experimenting. But I do enjoy the results: I like to eat good food, and I like to have power over what I eat. So I can and do cook everything from butternut squash chili, to carrot-top chimichurri, to sous vide turkey leg confit with tasty results.

Enjoying the results is key for learning a skill you don’t innately love. So what if the doing doesn’t thrill you? You’ve still got a reason to keep at it. Which is why we must aim for quick results to enjoy.

Lately I’ve been learning how to make French omelettes.

Have you ever had one? They’re the egg at its platonic ideal: a smooth, fluffy, custardy delight. I had my first at a little café in Carpentras, France, and it ranks as #2 on my Favorite Meals of All Time.

The French omelette is famously difficult.

So difficult, in fact, that for a long time the test for a would-be chef was one smooth and fluffy French omelette, perfectly cooked. (Not unlike the importance of good sales copy, or a choosing the right customer.)

Again: I’m no chef.

But I do have a knack for picking up new skills.

Here’s how I managed to go from “oh my god what happened” to “yep that’s a French omelette” in just one day and three attempts:

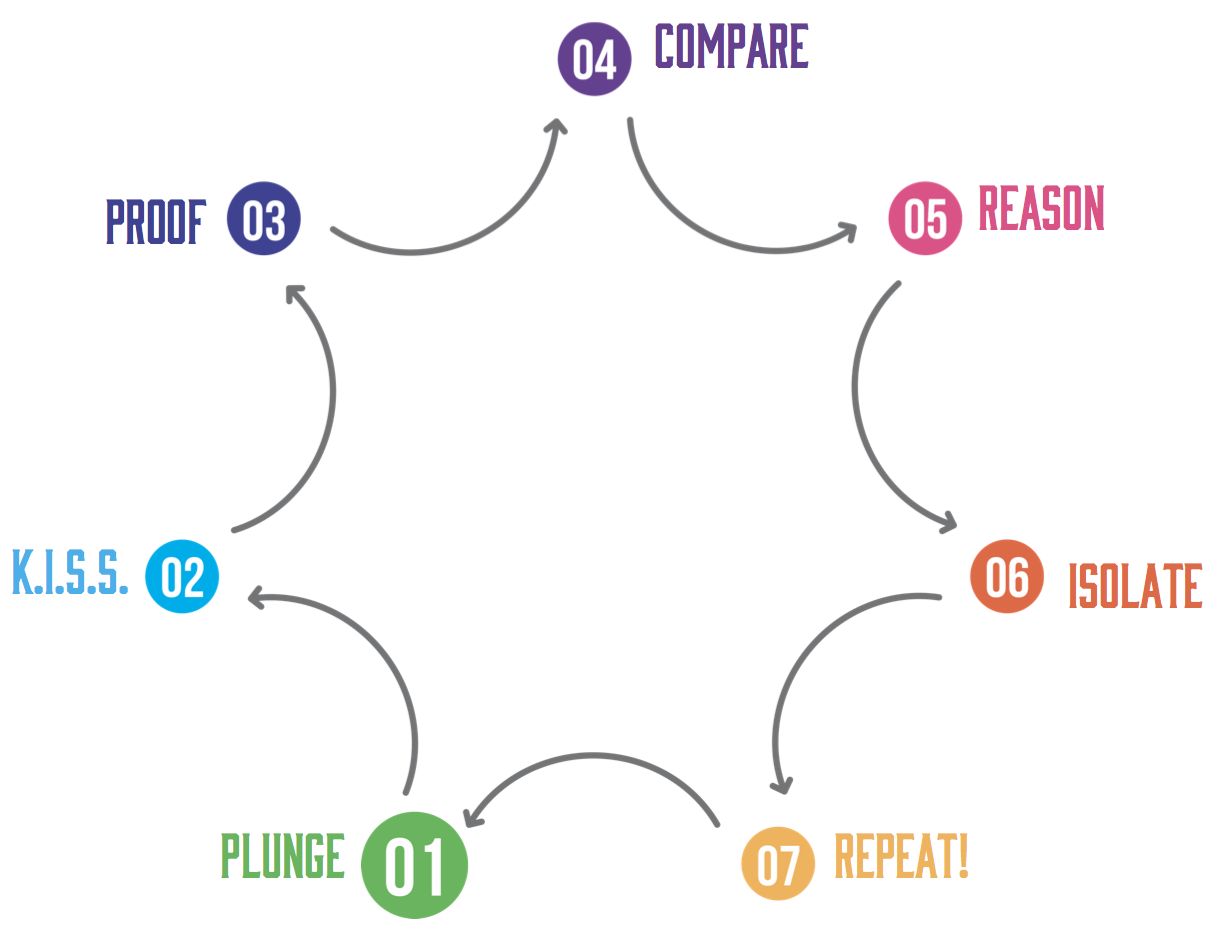

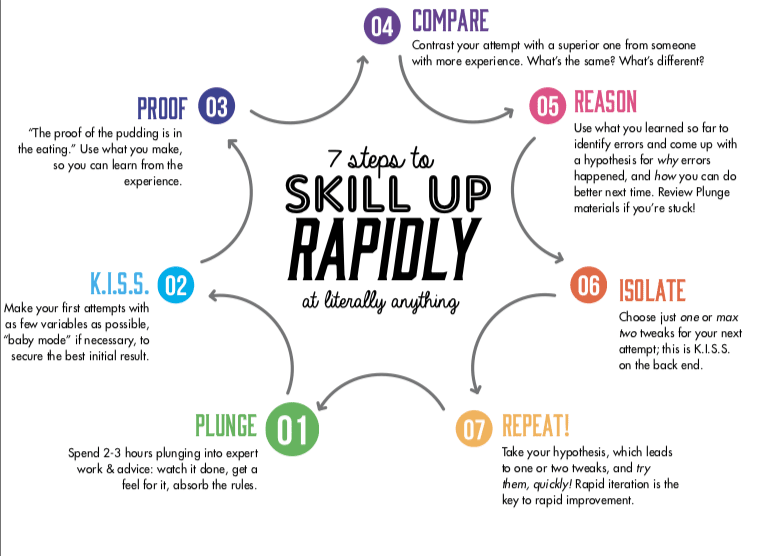

- Do a quick plunge into expert advice

- Set yourself up for success

- Proof your pudding

- Compare to a superior work

- Reason about your errors

- Improve one thing at a time

- Quickly try again!

This looks like a lot of steps but once you get into the groove, it doesn’t seem as complicated as it sounds. And yes, you can get into the groove, even if you’re not innately excited, because there’s something about this series of steps that will stoke your tiny flickering flame of rage to master. Even if it’s just an echo.

These steps will deliver rapid improvement and help you avoid the worst triggers for rage-quitting.

Level up your skills as fast as you can

Grab this handy cheat sheet so you can use my 7 steps to master new skills quickly!

When you subscribe, you’ll also get biz advice, design rants, and stories from the trenches once a week (or so). We respect your email privacy.

First: Do a quick plunge into expert advice

You’re used to things coming easy… and so when it doesn’t, when your first attempt bears absolutely no relation to what you imagined, you’re going to feel it even more acutely than someone who’s always had to struggle to learn. Do it my way instead.

A quick plunge into other people’s mastery is the first step to eventual success.

When I decided to make a French omelette, I started with research! I boned up on what a French omelette is, what makes it different from the omelettes I’ve made before, and how the experts do it, plus common mistakes.

To do this, I read three or four articles and watched five or six videos.

Here are a few things I learned:

- The classic way is to cook it extremely quickly over high heat, in a carbon steel pan

- But, you can get the same results with moderate heat and a nonstick skillet…

- You whisk the eggs until they are much runnier than for scrambled eggs or diner-style omelette

- No dairy in the whisked eggs

- Lots of butter in the pan… add the eggs when it’s melted but not browned

- Stir constantly in a circle until it’s time to spread out the egg curds

- If you’re fancy, you can roll the omelette just by shaking the pan in a very precise way

- But you can also just use a spatula

Important note: My quick plunge took me just an hour or two, *not* days or weeks. Beware the urge to procrastinate forever.

Suddenly I wasn’t just someone who had merely eaten a French omelette. I was someone who understood French omelettes. I could probably give a solid 5-minute talk on what they are, how they differ from American diner omelettes, what constitutes success, what ingredients to use, and how to prepare them.

That’s the goal of immersion: To get a sense of the operating rules behind whatever it is you’re going to learn. What are the components? What are the steps? Which are the most important, or the least? How does it work?

IN PRACTICE

Let’s say you’re trying to learn how to use content marketing to sell your first product. By diving into a few top-grade expert resources, you’ll hope to learn:

- How does content marketing do its job?

- What is the job, exactly?

- What are the types and formats used? What’s an absolutely smashing one look like?

- How about an easy one?

- What’s success look like for content marketing?

- Does it lead directly to a sale? (Hint: It does not!)

- What is the most important part of the equation, traffic, content, presentation, something else…?

In short, you want to understand your new skill’s operating theory.

But theory isn’t practice, and knowing is not the same as doing.

Second: Set yourself up for success

But it won’t work on every new skill, especially if you aren’t obsessive. Make it easy on yourself.

You’ll feel great if you succeed at hitting the low bar, or you can tell yourself, “Well, baby steps” if you don’t.

An early, epic failure with a big, hairy, audacious goal and many moving parts will cause even the most stout-hearted among us to falter. So: don’t do it.

For my first attempt, I chose to follow the video with the simplest instructions: non-stick pan, moderate heat, stirring with a plastic spatula, and a little water added to the eggs to make them thinner.

This is not the real way to make French omelettes. It’s definitely training wheels.

But I wanted to make it as easy on myself as possible. Which is important, because I screwed up differently every time:

- My first omelette wasn’t an omelette. The eggs devolved into large, separate curds before I had time to spread them out.

- My second omelette was much better… but to keep the custard layer thick enough to roll up, I had to limit my working space to half the pan.

- My third, I had to let it sit in the pan for quite a while after I spread it out, to set enough to roll up.

By making the omelettes “the easy way” with low heat and water, I was freed to focus on the fundamental skills of stirring, doneness, and folding.

IN PRACTICE

You’re about to start work on your very first intentional content marketing piece. Should it be a an hour-long video? Noooo. Should it be an epic 3,500 word essay? Nooo! Instead, how about a short piece that answers a question you’ve successfully helped folks with before? Ding ding! That’s a winning strategy. That empowers you to focus on the format and function of the marketing part, because the the content part already works.

When you reduce your difficulty level, you massively cut down your ‘surface area’ for flaws and make it that much more likely you’ll see some result. And that’s highly motivating. So, KISS!

Third: Proof your pudding

If you want to proceed quickly, use what you make.

I ate every last one of my attempts.

My first attempt was rubbery (but tasted pretty decent), my second attempt tasted good but was noticeably too wet inside. My third attempt looked and tasted like a French omelette. Mostly. But it was a little too thick on the outside and a little undercooked on the inside. I also forgot the salt.

I wouldn’t have known some of those things if I hadn’t put them in my mouth. That’s why they say, “the proof of the pudding is in the eating.” The proof in question isn’t a thing, buried in the dessert for some nursery rhyme reason — it’s an old noun meaning test. That saying is 400-some years old and relevant as ever.

IN PRACTICE

You’re going to ship your very first intentional content marketing piece. You’re not going to want to. You’re going to tell yourself it’s too crummy, it’s not going to do any good, you have the world’s worst CTA, nobody will read it, nobody will share it, it’s too basic and couldn’t possibly help everyone, everybody already knows that and who are you to do it anyway. That’s just the curse talking. Ship it anyway, and give yourself the gift of practical experience: the kind of knowledge you’ll never gain any other way.

You learn infinitely more when you use a thing and see how it performs at its intended task.

And eating rubbery eggs or publishing a poorly written blog post won’t kill you. It will only make you stronger.

Fourth: Compare to a superior work

But that quote’s about comparing your self to another person. Comparison of work product to work product is the Robin Hood of skilling up, like having a dedicated coach available 24x7 to point out specific areas for improvement.

Remember: You are not your work, every attempt is a good attempt, and every incremental gain is a huge win.

I know what a good French omelette tastes and feels like, so it wasn’t just a matter of having a meal, but also having a comparison. The real thing is smoother, fluffier, taller, and more tender than even my best result so far.

If you can see how your work measures up, you can know if you’re progressing.

Conversely, if you don’t compare your work to superior work, you can’t tell if you’re progressing, and you end up spinning your wheels indefinitely and eventually rage-quitting because nobody will stick to something forever without a sense of progress.

It’s a little bit tougher to compare large works like books, apps, courses. It’s easier to focus on smaller areas like headlines, CTAs, book structure or tone, or onboarding email sequences, feature designs, or code library features. And it’s still extremely valuable.

And here’s the thing: You can do comparisons on easy mode, too.

The first rule is to pick just one or two examples.

The second rule is to pick examples that are similar in scope to what you made.

The third rule is to pick examples that are good. I didn’t say perfection. I didn’t say by someone at the absolute height of their career. That’s one way to discourage yourself for sure! (The chef who made my comparison omelette isn’t famous or starred, he’s just a guy with a nice little café.)

‘Good’ means things that work well for their intended purpose given their constraints. That means omelettes that are both tasty and fluffy, software that gets used, lessons that help people, sales pages that convert, videos that get people engaged, emails that get opened, blog posts that get read and shared and used.

IN PRACTICE

Time to compare your content apples to apples. Seek out one or two people who are ‘making it’ in your same audience, and look at what they’ve been doing lately… and also what they did before, when they were starting out. If you wrote a blog post, look at a current blog post and an older one. If you hosted a live webinar or screencast, look for a pair of recordings, old and new.

Look for little details like headline, subheadline, hooks, structure, stories or facts, graphics or samples, content upgrades or no, what CTA they used, etc. If a recording, look for whether there was a structure, how they opened and closed it out, how detailed they were, how much they prepared, what their setup is like.

In addition to finding a few areas for improvement for your work, you’ll also see how your fellow creators have improved over time… and so can you.

Look for what they do well. And also for what mistakes they make!

And make no mistake: there’s always a mistake. Nothing is perfect. And seeing how imperfect things succeed is a deeply valuable lesson.

I’m pre-saging step #6 here, but focus on one or two things max.

Fifth: Reason about your errors

The errors for my first (scrambled) and second (sequestered-in-half-the-pan) omelettes were fairly obvious. The third one, having advanced past the most obvious errors, was a bit trickier. I could tell based on the texture that I cooked it too long. But I had to let it cook longer, or it would have been raw inside. Why? I wasn’t sure, at first. So I reviewed one of the other how-to videos to see what Jacques Pepin did.

The answer: I stirred slowly with a spatula; he stirred intensely with a fork.

I could only identify these errors because I had done that initial research plunge and understood (in theory) how the omelettes were meant to come together.

And if I hadn’t gone back to the pro material for a gut-check, I would have just had to try a million things until I stumbled on the answer (or gave up).

IN PRACTICE

Let’s say your post didn’t convert the way you liked. Unless you get direct and obvious feedback about readability or interestingness, you’ve got to work right on down the chain of steps and ingredients to figure out what didn’t go right. Did you get any traffic? Did you include a CTA? Does the CTA function? Does it stand out? Did the structure of your content draw the reader in? Did it help them, and make them want more?

That’s the real secret to improving rapidly from one attempt to the next: You must be able to reason about what’s wrong, so you can know what to try next.

Which brings us to…

Sixth: Improve one thing at a time

I’ll be honest and admit that I’m not so great at this rule. I’m a huge proponent of shipping things that are good enough to get the job done, but once I actually decide to improve them? Change is catnip to me (I love creating things!) and I want to fix aaaaall the inadequacies at once. That’s a bad habit I’m working on.

After the first omelette, I fixed the heat. After the second, I fixed the pan size. After the third, my stirring technique.

Tweaking just one thing is, effectively, the scientific method. It’s also the only way to test if you’re actually improving, rather than just flailing around like a chaos monkey.

IN PRACTICE

When you apply this to your content, keep it simple. Try things like: Improve the headline. Later, the CTA. Then improve individual sections of the copy separately. Work on one feature. Focus on improving leveling up just your audio quality. Rework one email.

Change one or max two of your techniques from the previous step, even when you’re going to start from scratch on a new version.

Seventh: Quickly try again!

Yep, I’m repeating myself… and that’s the key. Every time you run through this cycle, you’ll get better and better. Fast! You literally can’t see rapid progress without rapid cycling. The feedback cycle will allow you to bank up a bunch of tiny wins, and that will give you a little bit of that motivational high to keep you going.

To create success, eliminate failure

Yowza, we’re 3,500 words into this opus and it’s time to wrap it up.

My point in writing out this absurdly lengthy essay was to help those of you who are — as I once was — hobbled by the misconception that we should be great at everything.

I hope I’ve convinced you that there’s nothing wrong with you and that despite whatever you’ve experienced in the past, you can pick up new skills quickly and easily. Even if they’re not exciting. Even if they seem “alien.” If you’ve been telling yourself, “I could never” right up until this point.

And I hope I’ve convinced you that it’s worth it.

Robert Heinlein famously said that, “Specialization is for insects.” Frankly, he was a freaky weirdo with very distasteful ideas about humanity, but even a stopped clock is right twice a day. It turns out that early success can be a poison. And rage to master can turn against you. And that being very skilled can, absurdly, become a liability if you get stuck every time you try to branch out.

But when you follow my steps to overcome these pitfalls, and you diversify your portfolio — even just a little! — you’ll wildly multiply your options. Instead of relying on someone else to hire you as a laser-focused tool, you’ll be able learn how to build the career (or business!) you want.

Here’s a parting thought for you, my fellow RTM-blessed-and-cursed friend… one last Rage-quit Trigger Warning:

And that’s not only expected, not only okay, it’s actually fine and proper.

The world is full of successful people who’ve built their careers on the backs of just one or two superlative skills, bolstered by a portfolio of reasonably good ones.

You need to only be good enough to carry your best skills forward.

Just look at Bob Dylan: Superlative songwriter, poor vocals, so-so guitar work.

Thanks to the halo effect, your good-enough skills will glitter brilliantly alongside your excellent ones. If you take a moment to think about it, you’ll see that most people who are hailed as boundary-busting polymaths aren’t, really. And you don’t have to be, either.

My French omelettes will never be as good as Jacques Pepin’s, but Jacques isn’t going to show me up at brunch… so no one will ever know.

The seven steps you’ve learned today will be your harness and rock-climbing gear — with them, you’ll be able to escape any skill gap you find yourself in.

Even better, you’ve learned how to avoid falling into the chasm in the first place:

- Immersing yourself in a handful of expert guidance will give you a working mental model.

- Keeping it simple will make it easy to start.

- Using your work will give you invaluable feedback.

- Comparing your work to a superior one will keep your eye on the prize.

- Reasoning about errors will enable you to advance quickly.

- Tweaking just one thing at a time will cut the overwhelm and stress.

- Iterating quickly will give you great practice.

My parting challenge to you:

Pick one new skill this week that’ll help you build a more durable career, and work through these steps. You’ll be diversifying your skill portfolio in no time!

Egg hammock array, ahoy!

Level up your skills as fast as you can

Grab this handy cheat sheet so you can use my 7 steps to master new skills quickly!

When you subscribe, you’ll also get biz advice, design rants, and stories from the trenches once a week (or so). We respect your email privacy.